Hugo Chavez Is More Dangerous Dead Than Alive

Venezuela’s propaganda machine was at its best yesterday for the one-year anniversary of former President Hugo Chavez’s death. Or, as TV journalists with government-controlled Telesur described it, his “physical departure.”

The military parade held to honor the dead leader was clearly meant to proclaim the survival of his ideas. The event was a supercharged version of the cult of personality that surrounded Chavez in life. His successor, President Nicolas Maduro, and the country’s top military brass repeatedly referred to Chavez during the ceremony as their “supreme” and “eternal” commander.

The website for the state-run network Venezolana de Television wrote up the event as honoring Chavez “a year after his sowing.” And Maduro went a step further when he said: “Chavez has passed into history as the savior of the poor.”

A who’s who among Latin America’s extreme left took turns speaking in front of Chavez’s tomb. Bolivia’s Evo Morales seemed to sum up their collective thinking best when he said Chavez’s “fight will continue while capitalism exists.”

The day concluded with Telesur broadcasting “Mi Amigo Hugo” (“My Friend Hugo”), a documentary by American film director Oliver Stone. Stone’s 50-minute paean provided further evidence that the job of turning Chavez into a lasting international icon is well underway. The only thing more dangerous than a populist leader is the memory of a dead populist leader.

The challenge for Chavistas — as Chavez’s followers are known — is to rewrite Venezuela’s recent economic history. Telesur’s coverage helped their cause when it described Chavez’s first decade in office as “a decade won,” as opposed to the “lost decade” of the 1980’s, which included Latin America’s debt crisis.

The Telesur piece also suggested Venezuela had tripled the size of its economy under Chavez. It failed to mention that Venezuela’s growth came thanks to a global commodities boom and in spite of Chavez’s anti-business policies.

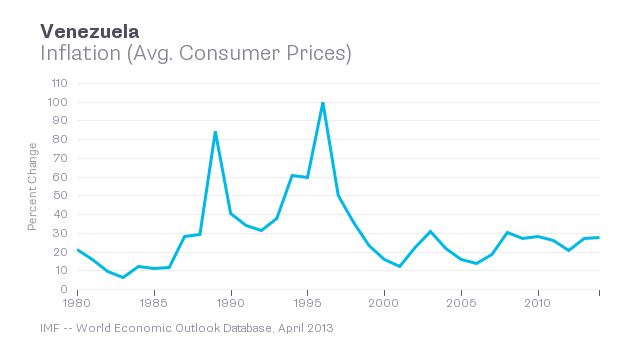

Telesur reporters managed to massage the data enough to argue that Venezuela’s inflation during Chavez’s first decade in power was lower than the preceding one. It’s true that Venezuela saw 100 percent inflation in 1996, two years before Chavez took office. But 18 years later the country’s inflation rate is again among the highest in the world.

The damage done by Chavez goes beyond Venezuela’s runaway inflation and its shortages of staple goods. His worst legacy has been to make economic dependence on the state a more palatable, and even desirable, way of life for a new generation of poor Venezuelans.

The former leader convinced his countrymen that state generosity was the same as sustainable economic development, that entrepreneurship and innovation were meant only for selfish elites, and that understanding the principles of economics and business was a waste of time.

Many Venezuelans are still unable to connect the dots between Chavez’s policies and the economic difficulties they face every day. Enough people continue to believe that their former leader’s benevolent redistribution plans were somehow only botched by state inefficiency.

Chavez’s version of social inclusion set a low bar. It never gave the poor the tools to achieve sustainable development through viable long-term employment in a thriving private sector. But nurturing people’s ambition has never been the Chavista way.

Hector Rodriguez, Venezuela’s education minister and a Chavez protege, recently articulated the Chavista credo better than most when he said: “We won’t pull people out of poverty into the middle class so they can later aspire to become [wealthy].”

Under Chavismo’s binary ideology the “people” include all those who happened to support their leftist regime. Anyone else is part of a right-wing conspiracy.

Venezuela’s economic implosion, when it finally comes, will leave behind a mass of entitled Venezuelans convinced that there was once a man who almost saved them from poverty. Tragically, they may decide to wait for another leader just like him to rescue them again.

Share this