Imagine the unimaginable

One of the biggest problems of our time is our increasing inability to imagine adversity. A fundamental use of imagination is to conceive of and prepare to overcome worst-case scenarios, a skill I call “negative imagination”. Living in prosperous, peaceful, and technologically advanced societies is killing our ability to imagine the worst because we are shielded from it – your mind cannot imagine what you do not know.

We are losing the ability to imagine trouble at a critical time, because the more interconnected and complex our businesses and societies become, the more things can go wrong. We like to believe modern abundance and comfort free us from the worries of our past, and the troubles of less advanced nations. But a lack of negative imagination makes us less prepared to overcome future difficulties, in fact it invites trouble, and this makes us less free.

When something becomes unimaginable it becomes dangerous. The 9/11 Commission famously concluded that the biggest failure ahead of the terrorist attacks was America’s “failure of imagination”, which has only emboldened enemies of liberal democracy. Think of Russia’s meddling in the 2016 elections, stronger dictatorships and populist governments around the world, and the arrival of fake news with social media. All of it was unimaginable not long ago. A lack of negative imagination also caught the world unprepared for the pandemic that has infected more than 100 million people so far.

The more we experience adversity the more we can imagine it. Swedish neuroscientist David Ingvar found that the prefrontal lobe which helps us plan for and imagine the future is also where we store memory. The more limited our memories and experiences, the less raw material we have to imagine permutations of what’s to come. This is the downside of constantly avoiding hardship, physical discomfort, or being offended.

Instead we overprotect ourselves and our children convinced that avoiding negative thoughts is the way forward. Religion, politics, business, and society more broadly advise us to stay positive. Even a multibillion-dollar industry of psychologists and motivational speakers sells us the idea of perennial positivity. It is no wonder that anticipating and preparing for adversity is often mislabeled as pessimism and seen as unnecessary in our lives.

Negative imagination is crucial for success in leadership, business, and life. Doctors, lawyers, politicians, police officers, business or military strategists, cyber security professionals, and what I do, risk management consulting, are just some jobs where people succeed or thrive with the ability to anticipate the worst possible outcome. Ignoring this is misunderstanding what it takes to be successful in an increasingly uncertain world.

George Soros’s father paid a Budapest government official who confiscated Jewish property, to take his son on as his fake Christian godson so the young Soros could survive the Holocaust. Soros credits what he calls his “experience of evil” with his ability to think ahead and anticipate events. Kristalina Georgieva, head of the IMF, saw her Bulgarian family lose their property and faced hunger under communism. She now warns of the negative effects of austerity, which economists brought up in prosperity have a hard time imagining.

Negative imagination involves using what ifs. If my wife and I were to die and leave the kids behind, who takes care of them and who manages any money left? At home, we’ve built a plan around that idea. To avoid the chance of leaving orphaned kids, I often suggest to my wife the unromantic idea of taking different flights when going somewhere as a couple, in case something happens (the US president and vice president never travel together, I argue). Understandably, she hasn’t taken me up on that yet.

Negative imagination involves using what ifs. If my wife and I were to die and leave the kids behind, who takes care of them and who manages any money left? At home, we’ve built a plan around that idea. To avoid the chance of leaving orphaned kids, I often suggest to my wife the unromantic idea of taking different flights when going somewhere as a couple, in case something happens (the US president and vice president never travel together, I argue). Understandably, she hasn’t taken me up on that yet.

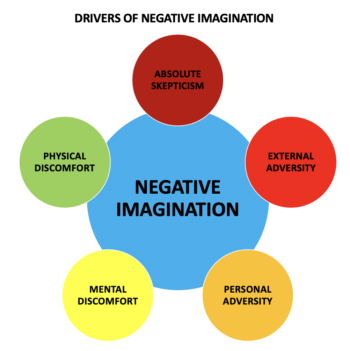

The good news is we can all cultivate negative imagination and we can do this by focusing on its five drivers:

Absolute skepticism: Approach everything in life as if it were something new, deserving of scrutiny. This means putting people, institutions, and ideas through the ringer to gauge their intent and capacity to do what they claim they can do.

External adversity: Living through dictatorships, wars, economic depressions, pandemics, in the right dosage, can provide rich raw material to become stronger, wiser, more imaginative human beings.

Personal adversity: The loss of a spouse, personal ruin, being fired or laid off from jobs. All of us have experienced one or more of these and can use these to feed our negative imagination.

Physical discomfort: This is a type of adversity we can impose on ourselves. Engage in some form of physical work on a regular basis, use public transportation, and avoid as much as possible having assistants or gatekeepers. Comfort separates us from the real-life experience of most people, and stifles our imagination.

Mental discomfort: Engage with people who hold political opinions, religious views, and lifestyles different than your own and understand their thinking and their problems. We discussed this in my previous post “Read things that tick you off”. No idea or belief should be too sacred to stress test.

The goal is to embrace controlled adversity and discomfort to stimulate our imaginations. In a future increasingly threatened by new forms of adversity, those capable of imagining the unimaginable will be better prepared to succeed.

What I’m (Re) Reading

The novel We by Russia’s Yevgeni Zamyatin (published in 1924) is considered by many the true precursor of dystopian fiction. In fact, George Orwell openly credited Zamyatin as an inspiration for his novel 1984. Aldous Huxley denied that We ever inspired his Brave New World, but its focus on the conflict between the modern versus the primitive side of humanity bears strong similarities to the story line in We.

The novel We by Russia’s Yevgeni Zamyatin (published in 1924) is considered by many the true precursor of dystopian fiction. In fact, George Orwell openly credited Zamyatin as an inspiration for his novel 1984. Aldous Huxley denied that We ever inspired his Brave New World, but its focus on the conflict between the modern versus the primitive side of humanity bears strong similarities to the story line in We.

The truth is We is a far more elegantly written and insightful book than Brave New World, in that it gets to the crux of how people’s imagination can become a problem for those in power. In We, the main character D-503 is a non-complacent, curious, spacecraft engineer who is a non-conformist in a reality where free thinking is dangerous to OneState. In the story (semi spoiler alert) OneState comes to the conclusion that to “extirpate the imagination” of human beings is the only way to finally bring about stability and contentment for people.

Imagination is a problem because it allows people to anticipate the future, with all its positive and negative aspects. Getting rid of it keeps people forever focused on the present, which is something real life dictatorships rely on to keep people pliant and obedient. Autocracies have often found that making people feel insecure and hungry makes them focus on survival and less on concepts like democracy or freedom.

The book’s lesson is that when we focus too strongly on eliminating envy and offense, in a bid to eliminate crime, human beings go overboard (as we usually do), and hurt one another instead. As a member of the OneState apparatus argues in the book: “the only means to rid a man of crime is to rid him of freedom.”

Share this